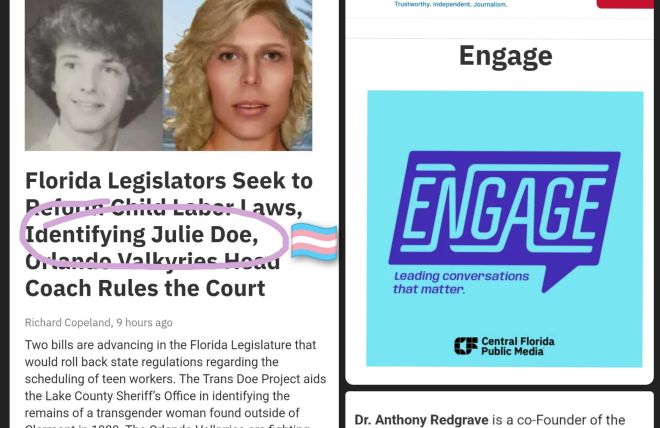

Last weekend, I traveled to the University of New England for my formal hooding and commencement ceremony for my Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership degree, although my doctorate was officially conferred many months ago. My dissertation, “Needs-based Standards of Practice For the Use of Forensic Genetic Genealogy in Investigations of Violence Toward Marginalized Victims,” is the culmination of years of hard work, getting to the bottom of difficult problems and looking for solutions for them. I’m not that different from the people for whom the Trans Doe Task Force seeks justice. When I look back, I can see how fortunate I am just to have survived.

Pursuing a terminal degree was not easy for me. That is not to say it is truly easy for anyone, but it is certainly easier when you come from a privileged background, have the financial and emotional support of your family, and are physically healthy. I did not have these things. When I was in school, I was the target of bullying based on my gender expression. I became very ill halfway through my Senior year in 1999, and missed several months of school. When I returned, the administration informed me that I would have to repeat my Senior year in order to graduate. I refused. I do not regret this decision, even if it caused other problems in my life.

As a disabled Trans person who didn’t finish high school, paying out of pocket for my hormones and continuing to survive was nearly impossible. I participated in paid medical research to fund the early stages of my transition in 2005. Surgery seemed entirely out of the question. Past a certain point, I realized it was no longer safe to live in my home town and I needed to move to a state that was safer for Trans people. When I met my husband, Lee, I was living in a friend’s hallway and sleeping on a futon mattress folded in half on the floor. We’ve been through a lot together – more than I’m able or willing to express here. Lee, and other members of the Trans community, supported me in being able to get my GED and go back to school. I received a small but crucial scholarship from Invisible No More, a Trans-run advocacy organization, to pay for my high school equivalency test. I also received tutoring over video calls from other Trans friends to get me through the subjects I felt I struggled with the most. I passed, and was able to go to college on student loans and scholarships.

It was during the process of getting my bachelors degree in 2018 that Lee and I began working on the very first forensic genetic genealogy cases. Forming the Trans Doe Task Force then became the reason I kept going further. After I completed my bachelors degree, I decided to get a masters degree in Instructional Design and Technology so that I could create training programs for this new and very important field. What I discovered along the way was that the persistent disregard for cases of hate-based violence toward Queer people in favor of solving white, cisgender, heterosexual cases was mirrored in the way that my experiential authority, and later academic authority, was disregarded as less important and valid than cisgender, heterosexual voices. I became aware that in order to get anyone to listen, I would have to continue my educational path to a terminal degree. So, I decided to go for my doctorate.

Throughout my educational experience, I faced many challenges, but hardly any of them were from my studies. The struggles I faced primarily were those unfortunately common to the experiences of Transgender people – the struggle to meet basic needs, the struggle for respect, the struggle to be seen as a person, let alone as an equal person. I also faced medical challenges, and parenting challenges. Working on my dissertation kept me going. I knew my study was important, because the people I was working to represent in my study are important, because they are my people.

Only 14.4% of people in the United States have a masters degree or higher. Only 6% of doctoral students are LGBTQ+. There are massive barriers to prevent intersectionally marginalized people from attaining higher education. If you are LGBTQ+, know that you have the right and the ability to take up the space you deserve, and doing so will pave the way for those who come after you. It’s not easy, but you are worth reaching for your goals.

The fight for justice for Trans and Queer lives isn’t just against bigotry and hate-based violence, or the negligence of law enforcement over many decades. It’s against gatekeeping, ignorance and apathy from researchers and institutions with the authority and ability to change hearts and minds through education. If you are a cisgender heterosexual person and this statement makes you feel uncomfortable, that’s good. It should make you feel uncomfortable. Now take that feeling, and do some good with it. If you are a straight, cisgender academic, please encourage your LGBTQ+ colleagues to step forward, and support them in doing so. If you run an academic or professional conference, you need to do more than just advocate for inclusion or say you value inclusivity. You need to remove barriers that prevent marginalized people from attending and being heard. Give scholarships to LGBTQ+ students who want to attend. Carve out time in your conference schedule to specifically reserve for LGBTQ+ scholars and professionals, and comp their attendance and travel costs. If you are a cisgender professional or academic and you want to be involved in LGBTQ+ issues, you need to find Trans and Queer professionals to not just add to your project, but to put in leadership positions. If you are a journalist or researcher, do not use the research of Trans and Queer organizations without asking or giving credit. Ideally, Trans and Queer professionals should be in charge of Trans and Queer research and projects instead of just being treated like research subjects or token team members. Having one Trans or Queer person on a team doesn’t mean you’re being inclusive. That one person is likely afraid to speak up.

In order for our voices to be heard, we have to be given a platform or take it ourselves. We have had to rely on our own people in our community to lift each other up and support each other in taking up space and getting louder. It’s time for everyone to lift us up.

If you would like to read my dissertation, “Needs-based Standards of Practice For the Use of Forensic Genetic Genealogy in Investigations of Violence Toward Marginalized Victims,” it is now available on Amazon in paperback or kindle, with hardcover coming soon.

If you would just like to read it as a PDF file in the digital UNE library, you can do so here.

I would like to close this by sharing the dedication from my dissertation:

For Aubrey, Benji, Bill, Christa, Dymun, Evon, Heather, Jamie, Julie, Justine, Kim, Koko, Lars, Nancy, Paula, Poppy, Sage, Simmoni, Tatiana, William, Za’niyah, and far too many others.

I will always leave the ninety-nine to find the one. I would want to know there was someone looking for me, too.